Gioachino and the Great War

By Romina Monaco

Gunfire erupted across the open field. Crouching behind a stark mulberry, Juchin studied the terrain. The barbed-wire was only a short distance ahead but he knew crossing the river would be too dangerous now - if not impossible. He would have to take his chances and head back to the trench. Beads of sweat trickled down his temples, dripping off his rugged jaw. Mustering the courage, he took a deep breath and ran while the steady, roaring gunshots echoed the pounding of his pulsating heart.

Juchin bolted across the muddy Isonzo plain tightly grasping his riffle. “I have to stay alive!” he thought as the mirage of his young boy, Beppo, stood before him guiding him home and to safety. Suddenly he felt a sharp, smoldering pain on his side and he tumbled to the ground. Lying on his back, gazing up at the grey sky, the image of his young son had all but dissipated into the smoke-filled air. A set of strong hands grabbed his shoulders and began to drag him roughly. He could feel the warm blood spewing out from his skin. “I’m dying”, Juchin thought. His eyes slowly closed - shutting out the grim light.

Gunfire erupted across the open field. Crouching behind a stark mulberry, Juchin studied the terrain. The barbed-wire was only a short distance ahead but he knew crossing the river would be too dangerous now - if not impossible. He would have to take his chances and head back to the trench. Beads of sweat trickled down his temples, dripping off his rugged jaw. Mustering the courage, he took a deep breath and ran while the steady, roaring gunshots echoed the pounding of his pulsating heart.

Juchin bolted across the muddy Isonzo plain tightly grasping his riffle. “I have to stay alive!” he thought as the mirage of his young boy, Beppo, stood before him guiding him home and to safety. Suddenly he felt a sharp, smoldering pain on his side and he tumbled to the ground. Lying on his back, gazing up at the grey sky, the image of his young son had all but dissipated into the smoke-filled air. A set of strong hands grabbed his shoulders and began to drag him roughly. He could feel the warm blood spewing out from his skin. “I’m dying”, Juchin thought. His eyes slowly closed - shutting out the grim light.

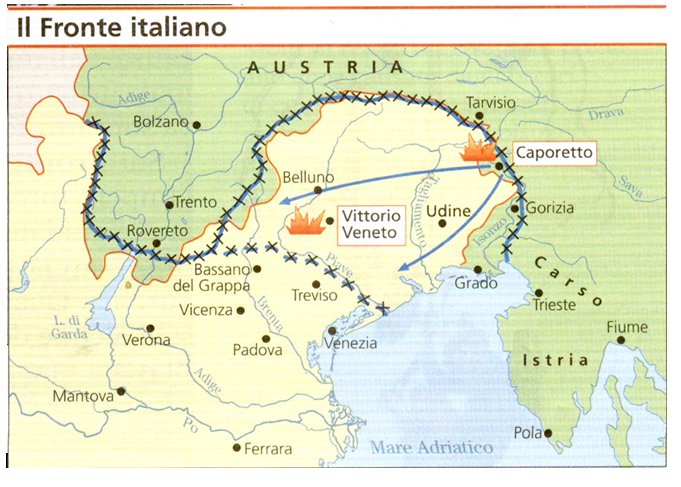

Sergeant Gioachino “Juchin” Menis was my great-grandfather and no, he didn’t die that day in late October 1917, during one of the grizzliest battles of the Great War. He did lose his left leg however, decimated by an Austrian hand grenade and later amputated at a military hospital. 11,000 men died in the Battle of Caporetto. He was one of the fortunate.

I think about him sometimes, especially on November 11th. He was thirty-three years old when he went off to war with his two brothers, Antonio and Agostino. Although they were not soldiers by profession they had each completed a one-year mandatory military service. Already married with two children, Juchin left behind his tranquil existence in the north-east Alpine countryside and enlisted in the Italian Second Army - picking up a gun and vowing to fight for King and country.

‘We fought for King Vittorio Emanuele’, Juchin would tell his children and grandchildren. ‘When he came to tour the military hospital we were in our beds, some without arms and legs…some had lost their minds…many lay dying. He just walked by, didn’t greet or even look at us”. I’m sure that while lying in that bed, yearning for the leg that had been brutally severed from his body, he wondered what it was all for.

I think about him sometimes, especially on November 11th. He was thirty-three years old when he went off to war with his two brothers, Antonio and Agostino. Although they were not soldiers by profession they had each completed a one-year mandatory military service. Already married with two children, Juchin left behind his tranquil existence in the north-east Alpine countryside and enlisted in the Italian Second Army - picking up a gun and vowing to fight for King and country.

‘We fought for King Vittorio Emanuele’, Juchin would tell his children and grandchildren. ‘When he came to tour the military hospital we were in our beds, some without arms and legs…some had lost their minds…many lay dying. He just walked by, didn’t greet or even look at us”. I’m sure that while lying in that bed, yearning for the leg that had been brutally severed from his body, he wondered what it was all for.

In August 2012 I traveled to the Carso region where Juchin had been injured. As I stood on the mount of San Michele looking out at the serene green pastures and the gentle current of the Isonzo River it seemed unimaginable that this had once been the stage of such mass carnage.

Recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the Alpine trenches of the Carso stir up some of the sensations and rawness of war. ‘Had Juchin been here?’I thought as I descended into one of the bone-chilling trenches. Staring down the narrow network of earthen corridors, I knelt on the dirt and leaned my back against the cold stone. ‘This is where they slept, ate and wrote letters to their families’, I realized. ‘This is where they died’. I had a lump in my throat and a profound heaviness in my chest. The sun was shining on that hot August day but in Juchin’s time the air would have been thick with artillery smoke and poison gas. It would have reeked of waste, death - and fear.

Recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the Alpine trenches of the Carso stir up some of the sensations and rawness of war. ‘Had Juchin been here?’I thought as I descended into one of the bone-chilling trenches. Staring down the narrow network of earthen corridors, I knelt on the dirt and leaned my back against the cold stone. ‘This is where they slept, ate and wrote letters to their families’, I realized. ‘This is where they died’. I had a lump in my throat and a profound heaviness in my chest. The sun was shining on that hot August day but in Juchin’s time the air would have been thick with artillery smoke and poison gas. It would have reeked of waste, death - and fear.

Just a few hundred meters away over 100,000 soldiers are buried in what is considered to be the largest war memorial in the country. Laid to rest within the WW1 monument of Redipuglia are 39, 857 identified and 60,330 unidentified Italian troops. While on their way to nearby Gorizia to visit family, Juchin would often ask his son-in-law to stop at Redipuglia. ‘This is where they buried my leg’ he would chuckle. Climbing the monument and reading the names of dead along the way, it occured to me that poor Juchin had never been able to climb the same steps in order to pay homage to his comrades. It was here atop this mass grave that I felt the true essence and tragic ramifications of war.

Considered one of the greatest conflicts in human history, the first world war differs greatly from the second. When all other avenues have been exhausted, to take up arms in the eradication of mass genocide and tyranny is, in my opinion, necessary. This seemed to be the case from 1939-1945. However, it’s altogether another matter when you are ordered to kill and risk your life so your head of state can obtain ownership of a piece of property. Ten million soldiers perished between 1914 and 1918, many of them dying for just a few hectares of land; The Somme, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge and Juchin’s Carso. Sixteen million civilians also died due to disease and malnutrition. In total, the Great War resulted in over thirty million deaths.

Considered one of the greatest conflicts in human history, the first world war differs greatly from the second. When all other avenues have been exhausted, to take up arms in the eradication of mass genocide and tyranny is, in my opinion, necessary. This seemed to be the case from 1939-1945. However, it’s altogether another matter when you are ordered to kill and risk your life so your head of state can obtain ownership of a piece of property. Ten million soldiers perished between 1914 and 1918, many of them dying for just a few hectares of land; The Somme, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge and Juchin’s Carso. Sixteen million civilians also died due to disease and malnutrition. In total, the Great War resulted in over thirty million deaths.

By the spring of 1918, the military hospital in Udine lacked provisions. With the sharp decrease in the male workforce as well as agricultural production, Europeans were starving - soldier and civilian alike. My great-grandmother, Melanie, walked to Udine every day from her village, a 40 km round trip, to bring Juchin food.

‘He would tell me to give the food to the other soldiers who had no one to take care of them. Many times he would go without so these poor souls could eat”, she would say.

He was in two military hospitals. Before Udine he had also been hospitalized in Milan. During his lengthy convalescence in both cities he became a secretary of sorts, writing letters for illiterate soldiers and reading their mail for them.

‘He would tell me to give the food to the other soldiers who had no one to take care of them. Many times he would go without so these poor souls could eat”, she would say.

He was in two military hospitals. Before Udine he had also been hospitalized in Milan. During his lengthy convalescence in both cities he became a secretary of sorts, writing letters for illiterate soldiers and reading their mail for them.

Juchin’s recovery was long and painful. There were no prosthetics then. The leg he was given was rudimentary and made of wood. Unlike today, psychiatric treatment wasn’t a part of the rehabilitation process. Perhaps being of assistance to his fellow soldiers not only helped to occupy his time but it also may have saved him from the depths of depression. How difficult it must have been to integrate back into society after participating in such atrocities and how could anyone relate except a fellow veteran? Perhaps he and his brother, Antonio found solace in their mutual pain while mourning the brother who never returned. Agostino was listed as missing-in-action in Albania. His body was never identified and to this day nothing more is known.

In the years following his recovery, Juchin went on to have other children, one being my grandmother, and the family continued to farm their land. The townsfolk knew him to be slightly authoritative but with a gentle, kind and very generous nature. During his twilight years, the tall blonde, muscular man who ran across the vast battleground of the Isonzo had morphed into a larger-than-life presence. He overcame adversity and forged on. Under the black fedora, a flowing white moustache framed his mischievous grin. His walking cane used to greet each passer by. He continued to sport his wooden leg which became a part of his identity as well as a symbolic reminder to all he encountered – not just of the tragedy of the Great War and all wars, but also of courage, survival and self-sacrifice.

On this Remembrance Day I would like to honour my Nonno Gioachino, not only for the obvious, but for the legacy he left behind. Through example he taught his children and every generation thereafter, that even in the darkest hour there is always God.

Rest in Peace

Gioachino Menis

Oct. 2nd 1882 – Aug. 28th 1965

Rest in Peace

Gioachino Menis

Oct. 2nd 1882 – Aug. 28th 1965

Map of the Carso

Gioachino with his children

Tony in the trenches of the Carso

Mount San Michele, Carso

Return to the Italianista Home Page

About Romina Monaco

Culinary

Cover Stories

Community